Winkston Tower is a mid-16th century tower house that was converted into a laird’s house in the 18th century and is notable for featuring some of the earliest gunloops and edge-roll moulding identified in Borders towers.

When the first castle was built at Winkston is not known however the site is thought to have been originally settled by an Anglo-Norman knight variously identified as Vink, Wink or Wynke, possibly in the 12th century. The site consists of a wide, flat-topped platform projecting west from rising ground to the east. There is evidence of possible terracing to the west while to the south is a burn later converted for use as a mill lade. The platform is elevated above an old route along the valley of the Eddleston Water. Any trace of an earlier building has been lost but traditionally the site of old Winkston was said to have been a short distance to the north-west of the present tower.

In November 1262 Alexander of Wynkistun is on record regarding a dispute with a Robert Croke over the moss at Waddenshope to the south of Peebles, but little else is written about the property until the early 14th century by which time it was in the hands of the Mowat family.

Edward III of England invaded southern Scotland in 1333 and effectively annexed much of the Border counties, with lands distributed amongst his supporters. Henry de Percy, 2nd Baron Percy, was granted numerous properties including Winkston which at that time was owned by William de Muhaut. Following the Treaty of Berwick in 1357 control of the Borders returned to Scotland, and in 1358 and 1359 the annual rent of Winkston was rated at 6 shillings and 8 pence.

Who owned Winkston at that time isn’t recorded, although it may have been Patrick de Malleville or Patrick Melville as in December 1365 he resigned the “all and whole lands of Wodgreuyntona, Wynkistona and Acolmefelde with pertinents” and David II granted them to William of Gledstanes, son and heir of the late William of Gledstanes.

In January of the following year David II also granted the annual rent from the lands of Wynkystona and Wodgreuyngtona to William of Gledstanes. However in January 1384 it was Henry of Douglas who was granted the annual rent from Malleville’s part of Wynkystone by Robert II. The reference to Malleville’s part suggests that Winkston may have been split into two parts by this time, with one part held by de Muhaut or Mowat and the other by Gledstanes.

Immediately to the south of Winkston are what were the temple lands of Winxtoun, so called because they originally belonged to the Knights Templar and later to the Knights of St John. They were known as Temple Bar and there’s now a house called Templebar situated to the south-east of Winkston. To the east of Winkston is Mailingsland which in old documents is written as variations on Meluinsland, Melvillsland and Melvingsland. It is tempting to suggest that Mailingsland represents Malleville’s part of Wynkystone although I haven’t been able to confirm this.

A division of Winkston would help to explain some of the discrepancies around ownership which continued into the late 14th and early 15th centuries. Undated charters of the reign of Robert III, dating them to between April 1390 and April 1406, grant the lands of Winkistoun to Willielmi Glaidstanis and the barony of Brochtoun, Winkistoun and Burelfield, along with the barony of Stanhouse, to David Mowat. Mowat was to hold the lands from the Hawdenes, David II having earlier granted the barony of Broughton to Edward of Hawdene.

In June 1406 Sir James of Douglas, brother of Sir Henry of Douglas, granted £3 annually from the lands of Wynkiston, Corstunyngiisfelde and Dillay-islande to a chaplain at his new collegiate church in Dalkeith, suggesting that the Douglases were still receiving the annual rent from Malleville’s part of Wynkystone.

John Deksyon of Wynkystoun, a bailie of Peebles, appears on record in 1434 as a witness to a land transaction, although when he was granted the lands of Winkston is unclear. Interestingly the Dicksons of Peeblesshire were descended from Thom Dycson, keeper of the Castle of Douglas in the 13th century and possibly a cousin of the Douglas family.

However in 1445 there is a sasine to David Mowet of Brochtoun and Wingstoun. William Dekyson of Winkston was made a burgess of Peebles in October 1475, Alexander Mowet received a sasine of Winkstoun and Burrelfeild the following year and Jhon Dickeson and Wylyam Dickeson of Wynkstown were bailies of Peebles in 1480. The Dicksons of Winkston also owned Smithfield Castle in the 15th century.

A land dispute in January 1489 may give some insight into the relationship between the Mowats and Dicksons or Dickinsons. Christian Mowat and her husband, George Wallace, took legal action against Patrick Elphinstone for wrongfully occupying and manuring her third part of the lands of Henderston and Newby and withholding from her 10 merks of the mails of the lands. Patrick Elphinstone claimed that he held the lands in tack from William Dikesoun’ of Wynkstoun’, bailie to Christian, and Dikesoun’ produced a letter of bailiary from Christian which showed that she had granted him the power to raise and collect the mails from the said lands and to let them to subtenants.

In March 1506 Alexander Mowat of Stanehouse, the great-grandson of the David Mowat who first received Winkston from David II, granted the lands of Stanehouse, in the barony of Stanehouse, the lands of Brochtoun, Winkistoun and Burofeild to John Mowat, his son and heir apparent. Eleven years later, after the death of Alexander “in his service as standard bearer”, and presumably also after the death of John, James IV confirmed the charter when it was noted that Alexander had “quitclaimed the said lands to Margaret Mowat, daughter and heiress of the said John”.

Margaret Mowat married James Hamilton of Raploch and died some time before 1534. In October 1536 her son and heir, James Hammiltoun, with the consent of her curators, Alexander Lokkart of Gleghorne and Thomas Hammiltoun of Roplo, sold the lands of Winkestoun to William Dikesoun, burgess of Peebles.

The date of 1545 is usually given for the construction of Winkston Tower, with William Dickson as its builder. This is no doubt informed by the existence of a lintel carved with that date, however it seems likely that there was some kind of tower here prior to that. In that year the Earl of Hertford destroyed Peebles in revenge for an English defeat the previous year and it may be that Winkston was also damaged at this time, and then subsequently rebuilt in 1545, although I have found no documentary evidence of this.

Tranter suggested that Winkston was originally similar in style to Barns Tower, which is thought to have been built in 1488 but was remodelled in the 16th century.

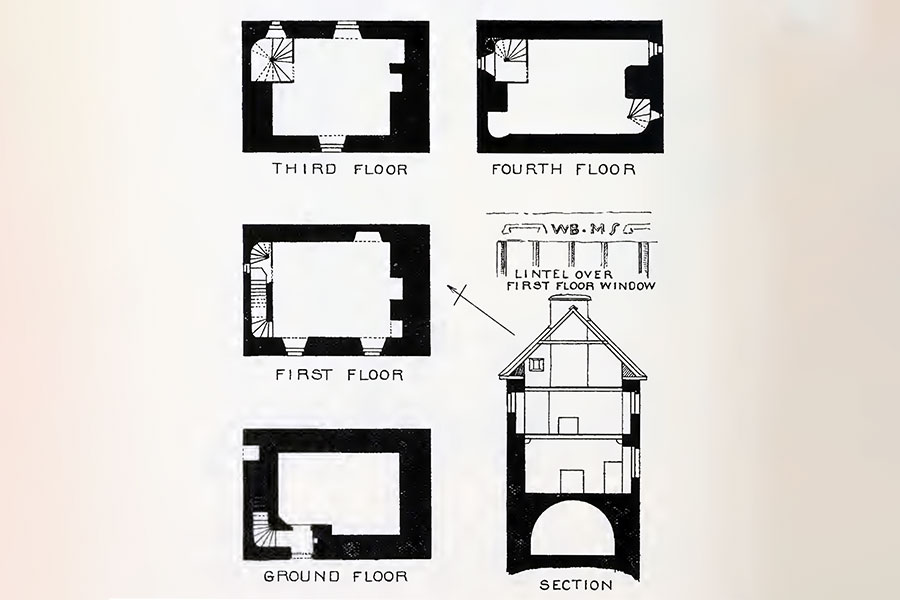

Winkston Tower originally consisted of at least three storeys, with a vaulted basement, a hall on the first floor and chambers above. Rectangular in plan, the tower is rubble-built from local whinstone with yellow sandstone dressings and measures approximately 10.7m south-west to north-east by around 7.6m with walls some 1.3m thick.

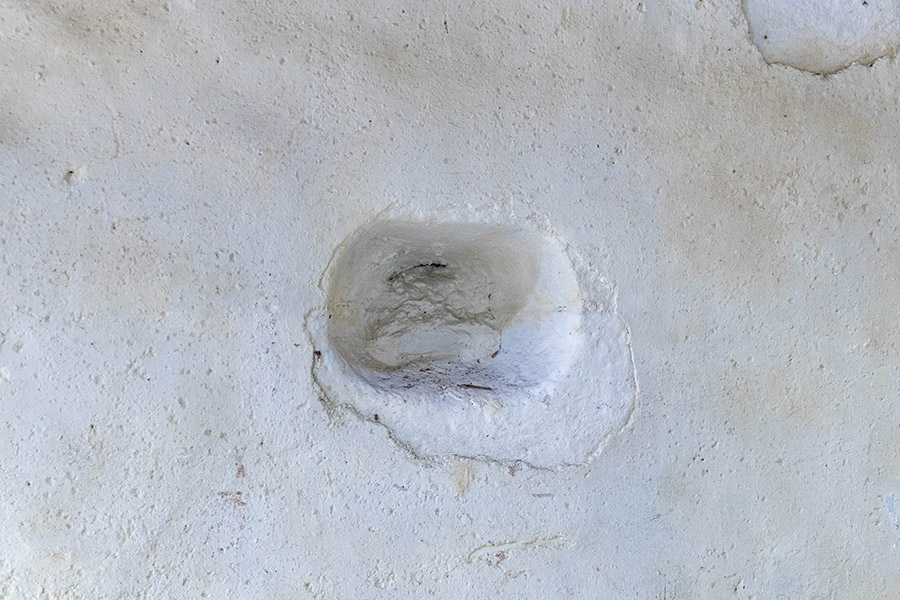

The ground floor was originally vaulted, although the vaults were removed in the 18th century, and features three oval-mouthed splayed gunloops. Each of the gunloops are centrally-located, in the north-east, west and south-west walls. These gunloops are thought to be some of the earliest examples of shot-holes for personal weapons found in the Borders, with those that were inserted into the walls of Hermitage Castle around 1540 being larger and intended for cannons.

It has been suggested, in part due to the lack of any visible evidence in the interior for a staircase due to the 18th century remodelling, that the tower may have originally had an attached stair tower. The north-east façade has been proposed as a location for such a tower, however the centrally-placed gunloop make this highly unlikely. The position of the gunloop on the south-west wall similarly discounts that as a likely location, although stones projecting from the base of tower at sub-floor level do suggest an extension of some kind or perhaps the remnants of an earlier structure.

There is enough room on the long north-west wall for a stair tower at either end, with the central gunloop, now obscured by a wooden lean-to, conceivably providing cover for an entrance in the bottom of a tower. The main south-east façade could also be a candidate for a similar tower however it is worth noting that Barns Tower doesn’t have an external stair tower. Instead a ground floor entrance on the left of the principal façade led into a lobby that gave access to the basement vault but also to an intramural staircase that led up to the first floor, from where a spiral stair rose nestled within the corner of the tower.

David MacGibbon and Thomas Ross, Edinburgh, 1889

Interestingly at the top right of the rear, north-west façade is a small opening which is reminiscent of the small windows found lighting staircases.

The interior of Winkston has been substantially altered over the centuries making it difficult to ascertain the original layout. At the north-east end is a large timber-linteled fireplace which is thought to be a later addition. Within the fireplace on its left is what has been interpreted as an aumbry or salt box, immediately to the right of which is the gunloop.

It may be that this was the location of an original fireplace, gunloops within fireplaces featuring in other towers, or it could be that the ground floor was originally used only for storage with the kitchen on the first floor. A second fireplace in the south-west wall, made from stone and bead-moulded but currently covered up, is also thought to be an 18th century insertion and blocks the gunloop in this wall.

The first floor has also seen significant changes from its original layout but would once have house a Great Hall, perhaps with a kitchen or adjoining chamber at one end. At the north end of the north-west wall is an opening in the wall with a smaller niche within it, perhaps representing a small blocked window.

Above this would have been further chambers on the second floor, and perhaps more on a third floor.

Externally the tower has also been significantly remodelled, particularly on the main south-east elevation where new door and window openings were made in the 18th century. A lintel inscribed with “ANNO DOM 1545” has likely been re-sited over a later doorway in the middle of the façade.

Photos from the 1940s show a slit opening above the left first floor window although this was later filled in.

The south-west façade features two fragments from the lower section of a damaged gunloop in the middle of the ground floor wall, and a large first floor window with chamfered edge surround, offset to the left. Slightly above and to the right of the larger window is a small central window with roll-moulded head and jamb, now blocked, which would have been at the original second floor height. Just below the eaves on the left is another small window with chamfered edge surround which has been interpreted as an 18th century addition to light the attic level but is at a strange height and position for that.

The north-west façade is obscured at ground level by a wooden chicken coop, covering the centrally-placed gunloop, but above it at first floor level is a small central window with chamfered edge surround. To the left of this and slightly lower is a blocked small window which would have lit the aforementioned recessed niche in the north-west corner of the first floor.

A probable 19th century single storey range has been built up against the north-east façade, within which the blocked gun loop can be seen at ground level. Above the roof of the extension is a small second floor window with chamfered edge surround, offset to the right and mirroring the window on the south-west façade.

In 1551 William Dickson received from Sir William Newby “a land and biggin” in the Northgait of Peebles which had formerly belonged to the parson of Stobo, however since Sir William had resigned them on his deathbed in favour of Dikesone they fell to the Crown under the terms of an old law. Dickson would later receive a Crown charter of the lands in August 1554.

The Dicksons seem to have had several disputes with the burgh of Peebles regarding common land or land owned by the town. In June 1552 William Dickson acknowledged that Carcado Bank was common land belonging to the burgh and not part of his property. Two years later in March 1554 John Dickson protested to the council that the lands of Quitehauch and Carcado Bank belonged to him and were not a part of Glentress which belonged to the burgh.

In April of the following year John protested that he didn’t know that the town had a charter to the same lands, and asked to see the charter. The burgh court of Peebles sat in the Tolbooth later that month and William was ordered against “molestatioun or trubbling purchessing of privat writtingis” against the bailies, council and committee of the burgh of Peebles regarding his son’s dispute over Quhithauch and Cardaco Bank “at the west end of Glentars”.

In March 1557 Andrew Dudingstoun of Southous made a reversion of the Temple lands of Winkstone to William Dickson, his son, and spouse, for 40 merks.

Despite their disputes with Peebles the Dicksons were seemingly still considered upstanding members of the community. William sat on the burgh committee in October 1556, and John was described as “an honourable man” when he appeared before it in April 1558. However the disputes seemed to continue as in October 1558 there was an intromission of Dikesone of Winkestone regarding the common. The lands of Winkston were bounded to the east by the Common of Winkston, a part of the common of Glentress which belonged to the burgh of Peebles, and at various times the Dicksons seem to have laid claim to some of this common land.

In October 1559 John was elected a bailie of Peebles, having received forty-three votes, and in February 1560 he was permitted to collect the small customs of Peebles for one year for a payment of 18 and a half merks, extended to a five year tack by Mary of Guise, the Queen Regent, in March of that year.

That December John and his son, James, were granted the feu right of “twa aiker and half of land callit Denis Park at the North Port of Peiblis” by the prebendary, Adam Colquhoun. The land, Dean’s Park, was to be held from the prebendary and his successors with an annual payment to the town of Peebles of one penny and their multure to go to the mills of Peebles. On the same day John and Katherine McGowane were included in a list of adulterers and fornicators who were encouraged to “mary or ellis abstene”.

In June 1561 Andrew Dudingstoun of Southous renewed his reversion four years earlier of the Temple lands of Winkstone, augmenting the original 40 merks by £40 making 100 merks overall.

The Dicksons witnessed various charters and attended burgh council meetings throughout the 1560s and John sat in parliament for Peebles in 1567, However in August of that year an arrest warrant was issued for “Dickson of Winkistown” and others for supporting the cause of James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell. Any fallout from this would appear to have been short-lived as the following year John Dickson was burgh commissioner for Peebles.

In March 1571 John and his brother, William, a bailie of Peebles, along with the burgesses Adam Bell, Johne Wod and Thomas Hesilhope, were compeared to appear before the Lords of the secret council in Peebles and declare, on behalf of themselves and the inhabitants of Peebles, that James VI was their only sovereign and that they wouldn’t communicate with Thomas Ker of Pharnyhirst, Thomas Ker of Caveris, James Ormistoun of Ormistoun, Master Johne Moscrope or any other traitors or notorious rebels.

The background to this was the forced abdication of Mary Queen of Scots and the coronation of her infant son as James VI, the Kerrs having supported the Queen. With instability in the country a “wapinshawing” or “vesying of the wappynis” was arranged in Peebles, for the local gentry to show their weapons in order to ensure that they were able to defend the area. It was recorded that the “the lard of Winkestoun elder; the lard of Winkestoun younger” were “armit”.

By 1572 John was Provost of Peebles but on the 1st of July that year he was “at length barbarously murdered” for “some cause unknown” on the High Street near Deane Gutter, the only holder of that office to be murdered. The following day William appeared before William Hay, 5th Lord Hay of Yester, and the bailies council and agreed, along with “his kin freindis sones barnes assitaris and parttakkaris”, not to molest or perturb anyone, and the council decreed that no-one would in turn molest, perturb or trouble him or his friends in body or goods. Later that month James Tuedy, John Wightman, Martin Hay, and John Bullo, all of Peebles, and Thomas Johnston, son of Thomas Johnston of Craigieburn, were all accused of John’s “crewale slauchter” but were acquitted.

In September 1578 James Dickson, apparent of Winkstoun, granted the lands of Denis Park “and barne thairof” to Patrick Dickson. On the same day he resigned “the tenement and ludging callit Denis Houss” into the hands of the bailies of Peebles and sasine was granted to Patrick. Whether these transactions refer to the same or neighbouring lands is unclear.

James resigned the 30 shilling land of Mailvingland, in the barony of Hundillishoip, and it was granted to Adam Dikesoun of Melvingland in November 1580. In February of the following year he resigned the lands of Winkistoun, extending to 40 shillings, with its tower, fortalice and manor, and they were granted to his uncle, William Dikisoun. Then in July William Dikesoun in Fowledge and James Dikesoun of Wynkstoun sold Winkston to Adam Tuedy in or of Dravay, and Jean Twedy, his spouse, and so Winkston passed out of the Dickson family and into that of Tweedie.

Winkston passed to Adam and Jean’s second son, John Tweedie, who was married to Elizabeth Hamilton, Lady Stenhouse, daughter of Sir James Hamilton of Crawfordjohn.

The Tweedies seems to have been a turbulent bunch and some time before 1596 Adam Tweedie, third son of Adam Tweedie of Dreva, and William Veitch of Kingsyde gave a bond by John Tweedie of Winkistoun not to harm James Brown in Wester Hoprew.

In 1600 John and Elizabeth were the subject of an entry of caution by Thomas Porteous of Glenkirk “in £1,000 not to harm certain tenants and indwellers in the upwode of Baith.” Three years later John, along with George Hamilton in Reston, was involved in some way concerning an unnamed person and the “demolishing of his house”.

Five years later John compelled Oliver Kay to sign a bond agreeing not to harm James Linlythgow, with Kay in turn guaranteeing that Robert Scott wouldn’t harm John, his wife, Lady Stenhouse, William Tweedie, fifth son of Adam Tweedie of Dreva, William’s sons, William, Adam and Charles, or James Tweedie of Denis.

Following the death of Adam Tweedie of Dreva, James Tweedie of Dreva was served heir to his father in the lands of Winkestoun although his brother John continued to be designated “of Winkston”.

In February 1617 John Tweedie of Winkestoun, along with his brother, James and James’s son, John, was subject to a horning and arrested for non-payment of debts. This doesn’t appear to have harmed their prospects as in November of that year James irredeemably resigned the lands of Winkistoun, extending to 40 shillings, with the fortalice and manor to his brother, John, who received a grant of them from James VI.

John’s son, James, was accused of killing Ninian Weir, brother of William Weir of Burnetland, in Edinburgh in November 1618 but was pardoned by the King the following month.

In January 1620 John resigned Winkston to Alexander Noble, a merchant burgess of Edinburgh, however he continued to be referred to as John Tweedie of Winkston during disputes with John Murray of Halmyre and the Paterson family in the early 1620s.

The Burgh of Peebles made a payment in March 1625 to carry “cripples” to Winkston, Edston, Myrehouse, Possae and Soonhope, and in April of the same year 10 shillings was “givin to cast ane gait besyde Winkstone that the kairt micht come to the towne”.

Another “wapinshawing” or “Wappen Shawing” occurred in Peebles in June 1627, taking place on the King’s Muir on the south side of the Tweed under James Naysmyth of Posso, Sheriff-depute of Peebles. Robert Porteous attended on behalf of the laird of Winkston with “a buff coat, a pair of pistols, and a rapier”.

The following month Alexander Noble was made heir to his father, Alexander, and received a charter of the lands of Winkston. Little seems to be known about his tenure however in January 1640 the signature of the lands of Winkstoun was granted to Helen Smith and Margaret Smith suggesting that the property was being used as collateral. In July 1643 he resigned the lands, which were then occupied by Patrick and James Leidbutteres, and they were granted by Charles I to James Littill in Foulage, in liferent, and to Adam Littill, his son, in fee

Despite the passage of time and several changes of ownership, disputes with the burgh of Peebles regarding the common land seem to have continued. In April 1652 the town’s magistrates spoke to the laird of “Cringiltie and Adam Lytill of Winkstoun, who have equall right with the toun of Winkstoun Commoun, and they togither te speak the Laird of Blackbaronie to caus his tennentes keepe thair goodes off the said Commone becaus he has no right thairto.”

This dispute seems to have rumbled on as in September 1656 the burgh council agreed to send two men or more to keep all goods belonging to the laird of Blackbaronie‘s tenants off the common of Glentres, and required the heritors of Winkstoun and Melvingsland to concur with the town. In March 1664 Adam Little apparently wrongly tilled a field on the common of Glentress and to avoid controversy James Williamsone, the burgh council’s treasurer, sowed “a pack or half a pack of oats upon the field” which would then be harvested for the town.

In February 1682 James Alexander in Menner mylne brought an action of poinding against John Hay of Haystoune and Adam Little of Winkstowne over a debt of £50 they owed to James Leadbutter in Menlingsland who in turn owed £46 to Alexander.

A signature of the lands of Winkstoun was granted to James and John Dewar in December 1684 and in 1685 Adam Little of Winkstoun appeared on a list of “disaffected persons” in Peeblesshire who disagreed with the Government’s repressive measures against the holders of conventicles.

It isn’t clear who succeeded Adam Little, described as “late” upon the marriage of his eldest son, William to Margaret Borrowman, the eldest lawful daughter of the late John Borrowman of Stewarton, in December 1700. An Adam Little of Winkstoun is listed for the shire of Peebles in an act anent supply in August 1704 but it isn’t clear if this refers to the late proprietor or perhaps another son.

Winkston Tower was extensively remodelled in the 18th century, possibly in 1734, to form a more fashionable and almost symmetrical laird’s house.

A new centrally-positioned main entrance was created in the principal façade, with chamfered arrises and surmounted by the re-used 1545 lintel. Either side of this new entrance were inserted new chamfer-arrised windows, the right of which is surmounted by a lintel inscribed with 17 ILG 34 or 17 ILS 34.

This inscription is often attributed to John Little, who was a tenant in Foulage, and his unnamed wife. However two years later a James Little, described as a merchant and son of Adam Little of Winkston, built the Virgin Inns building at the north end of the bridge over the Eddleston Water between the New Town and Old Town of Peebles. It’s possible that it was in fact he who was responsible for remodelling Winkston.

It has been suggested that the second doorway to the left of the main entrance was converted from a former window some time after the 18th century remodelling, possibly in the 19th century, however as mentioned above it’s possible that this was the original doorway. It’s also possible that it was the original doorway, was converted to a window in the 18th century in the interests of symmetry, then converted back into a doorway at a later date.

On the first floor were three further large, regularly-spaced windows with chamfered edge surround, all now blocked with the centre blocking recessed and the flanking windows flush. To the rear the gunloops were blocked and a new window inserted on the right at ground floor level. The upper storey or storeys were removed and a new pitched roof constructed featuring rubble gablehead chimney stacks without cans, leaving the house with a two storey plus attic arrangement.

Internally the basement vaults were removed and the space divided into left and right rooms by a wooden staircase leading up from the new entrance. The original staircase, whatever form it once took, was presumably removed at this time. A crosswall to the left of the staircase is often attributed to this period but may be a 19th century addition, the floors perhaps originally being divided by wooden panelling. The floor levels were changed in order to make more spacious rooms.

The north-east chamber on the ground floor became the kitchen, with the aforementioned large timber-linteled fireplace inserted on the north-east wall covering the gunloop.

The south-west ground floor chamber was probably used as a parlour and had a stone bead-moulded fireplace constructed over its gunloop.

Two further chambers on the first floor also feature bead-moulded fireplaces, with further accommodation or perhaps storage in the attic.

Windows just below the eaves on the north-east and south-west gable ends may have been added at this time but as discussed earlier their position so close to the roofline may suggest that they were in fact earlier.

Despite such extensive work carried out on the property, or perhaps because of it, just nine years later the signature of the lands of Winkstoun was granted to Alexander Stevenson of Smithfield in February 1743.

In 1761 part of Glentress Common, the commonty of Winkston and Heathpool, was divided between the surrounding heritors and the burgh of Peebles, presumably in an effort to put an end to the disputes over the common land. That effort was seemingly in vain however as in 1765 James Williamson of Cardrona, Alexander Stevenson of Smithfield and Alexander Murray of Cringletie all raised actions against the burgh of Peebles regarding the common of Glentress, “a name vaguely applied to a series of connected and detached hill-pasturages stretching from near Milkiston to Shielgreen, and including the common of Winkston”.

James Montgomery of Stanhope, Lord Advocate, was appointed arbiter but the action failed. In 1770 a fourth claimant joined the action, with John Patterson of Windylaws seeking “two or three acres” of the common of Glentress and “by mutual agreement, his claim was submitted to Mr Wightman of Mauldslee.” This time the claimants was successful and the town was left, “though not very securely”, with some portions including Pilmuir.

In 1773 Alexander Stevenson of Winkston and Smithfield raised a summons of division of commonty against the burgh of Peebles for the division of the common of Winkston, to which Peebles objected the following year however the land surveyor William Oman was appointed to measure and make a plan of the commonty of Winkston and Heathpool and it went to the Court of Session in 1775. The matter seems to have come to a head in 1779 when James Montgomery of Stanhope was again appointed arbiter over the division of the commonty of Winkston and Heathpool and the burgh of Peebles were allocated 135 acres adjacent to the commonty of Heathpool.

Alexander Stevenson, later Sheriff of Peebles, seems to have died before 1789 when his properties were inherited by his sisters. The lands of Winkston were advertised for let in 1792 when they were described as “mostly in a state of nature” and they were later bought by John Anstruther of Airdet (possibly a misspelling of Airdrie). It may have been Anstruther who was responsible for building the new farmhouse to the south of Winkston Tower.

By the mid-19th century the estate had passed from Anstruther to his grandson, Major John Anstruther Macgowan of the 93rd Highlanders, who died in August 1855 from wounds suffered at Sebastopol. The Major’s heirs sold Winkston to Robert Thorburn, a London artist, for £7800 in 1857 and it was occupied by a tenant farmer named James Scott.

By this time the tower had been incorporated into a single storey farm steading to the north-east. A small single storey extension with corrugated roof was built projecting south-east from the south end of the south-east façade of the tower, most of the towers windows were blocked and the interior was remodelled. The tower was used as a celebrated dairy, with Agnes Scott having published the pamphlet “Dairy Management and Feeding of Milch Cows: Being the recorded Experience of Mrs Agnes Scott, Winkston, Peebles” in 1861.

Winkston was farmed from the 1870s onwards by a John Cairns who also operated as an auctioneer from the property and he was followed by an Andrew Pringle Cairns in the 1910s. In 1913 and 1914 Andrew Pringle Cairns and Benjamin Tudhope were both listed as farmers at Winkston, with Tudhope being the sole farmer from 1915 into the early 1920s. David G. Crowe was the farmer in 1924 but he was superseded by Messrs Stewart who farmed Winkston into the 1940s.

Winkston Tower was latterly used as a farm store, and in the 21st century the chimneys were rebuilt to stop them from collapsing. Winkston is still run as a farm today, with some of the farm buildings converted for use as self-catering holiday accommodation and the current owners have plans to restore Winkston Tower as further holiday accommodation.

Alternative names for Winkston Tower

Weykstoun; Weykstow; Wingistoune; Wingston; Wingstoun; Winkestone; Winkestoun; Winkiestoun; Winkistoun; Winkistoune; Winkistown; Winkston Tower House; Winkstone; Winkstoun; Winkstowne; Winkystoun; Winlestoun; Winxstoun; Winxstoune; Winxton; Winxtoun; Winxtoune; Wynkeston; Wynkestoun; Wynkistona; Wynkistoun; Wynkistun; Wynkstone; Wynkstoun; Wynkstoun'; Wynkystona; Wynkystone; Wynkystoun