Glasgow, 1911

Glasgow Castle dated back to at least the 13th century but the last remains were cleared away in the late 18th century.

The first castle is thought to have been timber-built on a motte by David I during the second quarter of the 12th century although there is no surviving documentary reference and little archaeological evidence for it. Earthworks uncovered in the area may represent vestiges of this early castle although they could also be associated with a later building.

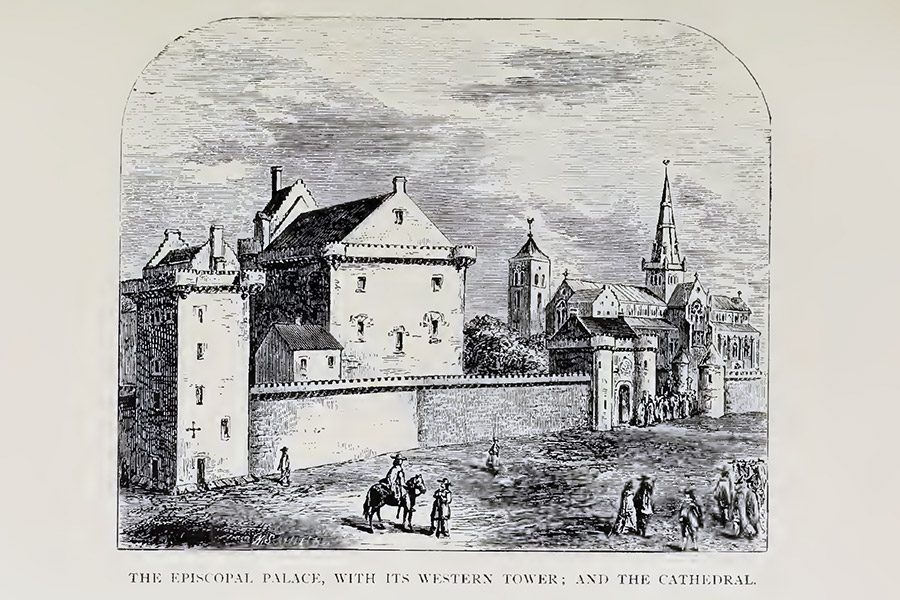

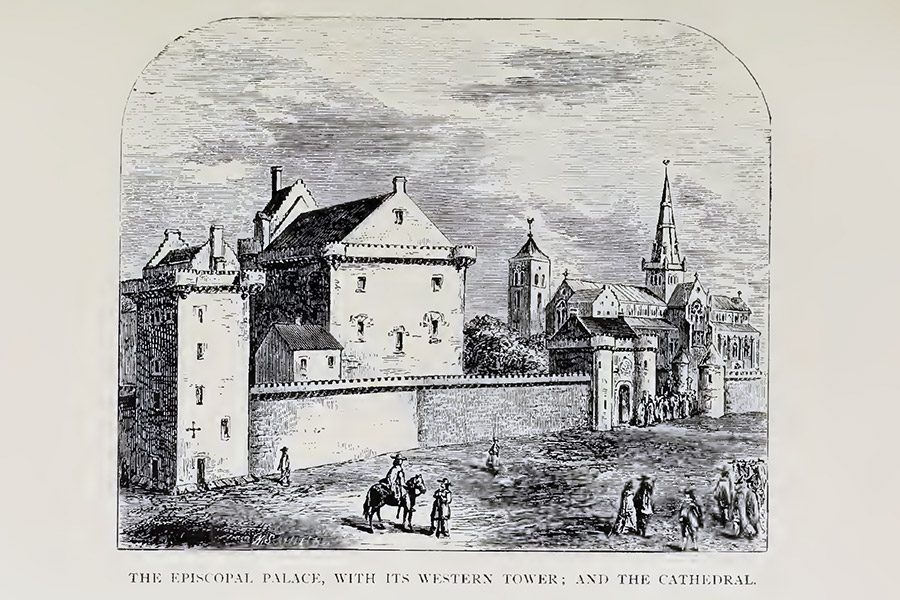

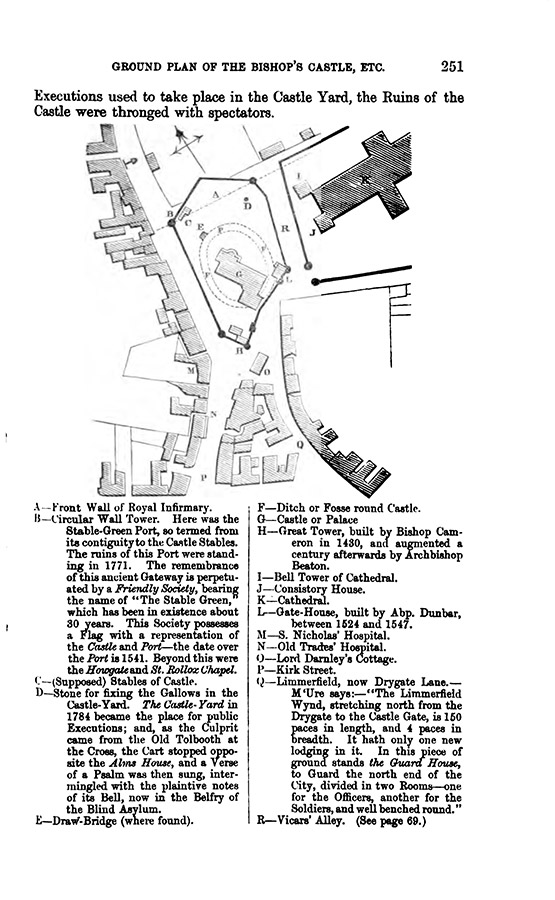

The castle was situated to the west of the 12th century Glasgow Cathedral which is reputed to be built on the site of St Mungo’s grave. Later a stone hall block containing a Great Hall with solar above was constructed on the western side of the earthworks. The first mention of the Bishop’s Palace, which was occupied by Bishop William de Bondington, occurs in 1258 when it is described as being situated “without” the Castle of Glasgow. Bishop William died in that year and was succeeded by Bishop John Cheyam who in turn died in 1268 when the palace was described to as “beyond” the castle.

The castle was occupied for Edward I of England by the Bishop of Durham, Antony Bek, in 1297 and was besieged and captured by William Wallace in the same year supposedly after the Battle of the Bell o’ the Brae, a skirmish in the High Street which may or may not have occurred. Edward spent three days in Glasgow in 1301 although it isn’t clear whether or not he resided in the castle.

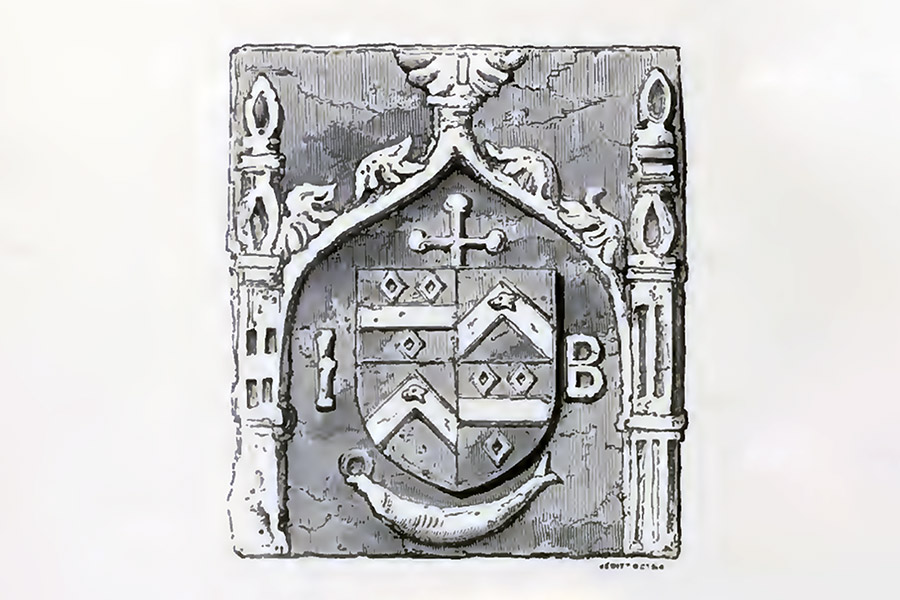

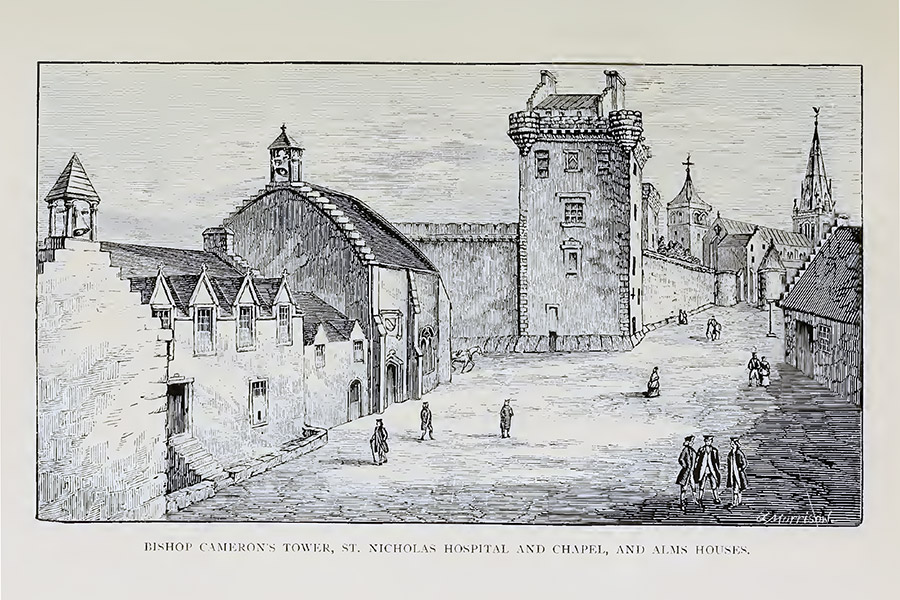

Around 1430 Bishop John Cameron built a large square tower comprising of four storeys, with a secondary wing extending from the southern side of its west wall. This wing had a much smaller footprint but was one storey taller than main tower. It isn’t clear if this was contemporary with the main tower or a later addition. A carved armorial panel on the tower carried Bishop Cameron’s arms along with a mitre and crozier. Known as the Great Tower, it shares striking similarities in design with the Bishop’s Palace of Spynie which is thought to have been built in the 14th century then remodelled in the 15th and 16th centuries.

At ground level in the main tower was a vaulted basement, probably containing a kitchen and storerooms. Above this was a Great Hall on the first floor which was entered via the west wall on an external stone balustraded staircase leading up from the courtyard. A large fireplace was located in middle of the longer south wall, and across a hallway to the west was a chapel housed in the wing room.

Above the Great Hall on the second floor was the Bishop’s bedroom, reached via a spiral staircase leading up between the Great Hall and the chapel. Above this was a further room, possibly divided. Above the chapel in the wing was a single bed chamber on each of the subsequent three floors.

The Great Tower was almost certainly surrounded by a courtyard wall of some kind, it being inconceivable that such a high status building wouldn’t have been afforded the additional protection of an outer wall and the old castle having had some sort of defences. While the earlier Bishop’s Palace had been outside the castle’s walls it seems that the new palace had been incorporated into an expanded castle by this time.

The courtyard is thought to have had its main entrance on its north side, with a drawbridge leading over a moat or ditch. Its ashlar walls were crenellated and featured bastions and rose to an estimated height of between 4.6m and 6.1m. They enclosed an irregular quasi-hexagonal area measuring around 91.0m north to south by around 55.0m east to west.

Glasgow, 1878

Six further Bishops succeeded Cameron before the bishopric of Glasgow was elevated to archiepiscopal status in 1492, with Bishop Robert Blackadder becoming Archbishop Blackadder. He died in 1508 and was succeeded by Archbishop James Beaton, the sixth and youngest son of John Beaton of Balfour. Archbishop Beaton is said to have been responsible for building the courtyard wall, although he may have remodelled and expanded earlier work.

He built a tall tower, which became known as the Bishop’s Palace, at the south-west corner of the courtyard walls, rising to a height of five storeys plus a garret. He also built small round tower, described as a bastion, at the north-west corner of the courtyard walls. His coat of arms, quartered with those of Balfour and below which was a salmon holding a ring in its mouth, are said to have been carved in various places around the courtyard wall.

Glasgow, 1880

Glasgow, 1880

During James V’s minority John Stewart, 2nd Duke of Albany (second creation), was appointed Regent and Archbishop Beaton was made Lord Chancellor. Albany was unpopular and in February 1515 John Mure of Caldwell attacked the castle, which was being used to store royal munitions, when the Duke was in France. Albany returned in May that year and retook the castle.

Archbishop Beaton raised a civil action against Mure in 1517 for compensation for the damage to the castle he had caused and the goods he had stolen. These included feather beds, stone, iron, pots, pigs, salmon, salt herring, sugar, meal, wine, barrels of gunpowder and guns. Mure was also order to pay 200 marks to Archbishop Beaton “for the scaith sustenit be the said reverend fader in the destructioun of his said castell and palice of Glasgow.” Later in 1517 the castle was attacked again, this time by Mure’s brother-in-law, John Stewart, 3rd Earl of Lennox.

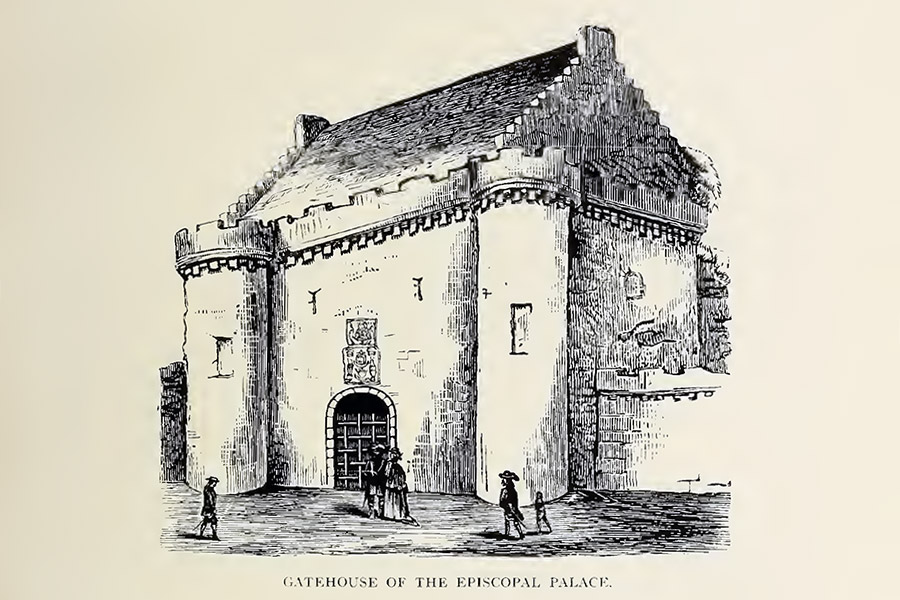

In 1522 Archbishop Beaton became Archbishop of St Andrews and was succeeded in Glasgow by Archbishop Gavin Dunbar, the third son of John Dunbar of Mochrum. He was responsible for building a large gatehouse built on the south wall towards the south-east corner of the courtyard. Featuring crow-stepped gables and a pitched slate roof around which was a wall walk, it had a central arched entrance flanked by twin round towers.

Glasgow, 1911

Above the entrance were two carved stone panels. The upper panel featured the Royal Arms of Scotland and below the shield was a smaller second shield carved with with “I 5” for James V. The lower panel carries the arms of Archbishop Dunbar, three cushions within a double tressure flory and counter-flory gules, with a mullet for difference, over a salmon with a ring in its mouth and between a pair of ornamental pillars. Below this was a further pair of pillars between which was carved the arms of James Houston of Houston, the sub-dean of the diocese, a chevron chequé sable and argent between three martlets of the second, with a rose in chief for difference.

Glasgow, 1880

A long stable block within the north-west corner of the courtyard may also date to this time.

In 1544 the castle was garrisoned by forces loyal to Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox, and William Cunningham, 4th Earl of Glencairn, as part of a conflict with the Regent, James Hamilton, 2nd Earl of Arran. Following the Battle of Glasgow Muir on the 16th of March Hamilton’s forced laid siege to the castle on the 28th, bombarding it withe artillery. The garrison eventually surrendered after 10 days, supposedly when the captains of the castle were promised gold by Cardinal David Beaton, the Lord Chancellor and nephew of Archbishop James Beaton, although they were instead hanged outside the Tolbooth. A meeting of the Privy Council was held at the castle in 1545 at which Mary of Guise was present.

During the Reformation Archbishop Beaton removed the valuables from the Cathedral to the castle but in 1559 Regent Arran seized the castle from the Archbishop and left a garrison in the castle under Alexander Cunningham, 5th Earl of Glencairn. French troops provided by Mary of Guise attacked and took the castle in March 1560 during the Battle of Glasgow. Later in 1560 Archbishop Beaton fled to France and Regent Arran reoccupied the castle before he was ejected by Lennox.

In May 1568 the castle was placed under the protection of Sir John Stewart of Minto, Provost of Glasgow, and later that year it was besieged by Archibald Campbell, 5th Earl of Argyll. Sir John successfully held the castle for Lennox when it was attacked by the Hamiltons in May 1570. The Earl of Lennox became Regent for his grandson James VI but was murdered in September 1571 and in 1573 the guardianship of the castle passed to Archbishop James Boyd of Trochrig.

The castle’s importance had faded however and it began to deteriorate. It was used to house prisoners although it continued as the seat of the Archbishop. In November 1587 Walter Stewart, Commendator of Blantyre and later 1st Lord Blantyre, was granted by Crown charter the lands and barony of Glasgow with the Castle of Glasgow as its principal messuage.

The charter was ratified in 1591 however soon after the lands and barony of Glasgow were granted instead to Ludovic Stewart, 2nd Duke of Lennox and later 1st Duke of Richmond, the son of James VI’s father’s cousin, Esmé Stewart, 1st Duke of Lennox. Archbishop Beaton however was still alive in exile in France and was restored in his offices and lands in 1598, however the restoration of the archbishopric excluded the castle.

In the same year the 2nd Duke of Lennox married Jean Campbell, the widow of Sir Robert Montgomery of Giffen and the sister of Sir Hugh Campbell of Loudon. Repairs were carried out by the Duke and Duchess and they seem to have used the castle as a residence from 1599, the Duke granting a charter “in the duke’s chamber (cubiculo) in the castle of Glasgow” to Thomas Craufurd of Jordanehill of the lands of Cult in the dukedom of Lennox which Robert Stewart of Southbar had resigned.

In December 1600 James VI granted to the Duke of Lennox “the castle of Glasgow, with houses, buildings, yards and greens (viretis) thereto belonging; with liberties, privileges, and pertinents; also the right of nomination and yearly election of the provost, bailies, and other officers and magistrates of the burgh and city of Glasgow, as freely in all respects as the archbishops of Glasgow formerly had”.

The work was completed in 1601 and in 1602 the Lennoxes entertained James VI when he stayed at the castle. However the following year the King left for England with the Duke of Lennox accompanying him. With the Duke and Duchess now living apart the Duke granted the castle to his wife for life where she remained with their children until moving to Inchinnan, dying there in 1610. In 1611 Archbishop Beaton’s successor, John Spottiswoode, ordered the castle to be restored. Seemingly the Duke of Lennox continued to own the castle but the Archbishop was permitted use of it.

In 1635 the castle was described by the English visitor Sir William Brereton, 1st Bt., as “a poor and mean place”. Charles I granted a charter of all the lands formerly belonging to the Archbishops of Glasgow, including the castle, to James Stewart, 1st Duke of Richmond and 4th Duke of Lennox, in 1641. In 1659 George Maxwell of Pollok was granted a commission by Mary, Duchess of Richmond and Lennox, to represent her young son, Esmé Stuart, 2nd Duke of Richmond and 5th Duke of Lennox, at the castle during the election of the Provost of Glasgow.

Following the restoration of Charles II in 1661 Archbishop Andrew Fairfoul resided at the castle. Between 1674 and 1675 repairs were carried out under Archbishop Alexander Burnet at a cost of £651 Scots. The castle was apparently damaged in 1679, probably around the time of the Battle of Bothwell Brig. Further work was carried out under Archbishops Arthur Rose and Alexander Cairncross between 1680 and 1686.

Following the flight of James VI in 1688 an anti-Catholic mob attacked the castle which Archbishop John Paterson duly surrendered and in 1689 it was described as “in ruines” apart from “what was the ancient prison” meaning Bishop Cameron’s Great Tower. With the abolition of Episcopacy the castle, along with the other possessions of the archbishopric, became Crown property.

In 1693 estimates were drawn up for repairs to the castle which had suffered neglect and vandalism. all of the chimney heads were said to be ready to fall, all of the roofs required remedial attention, the courtyard walls needed repointing, the gatehouse was in a particularly bad way and the staircase from the courtyard up to the entrance of the Great Tower would need to be rebuilt and missing or broken balusters replaced. The total estimate came to £783 13s 4d Scots.

Theatrum Scotiae

London, 1693image courtesy of NLS

The work was approved by the Treasury and £100 Sterling (£1200 Scots) was granted to John Hamilton of Barncluith to carry out the repairs under the guidance of the Duke of Hamilton. It isn’t clear if all of the work was carried out, and while the buildings were made watertight and secure not all of them were habitable.

Glasgow, 1911

In 1696 William II granted Alan Cathcart, 6th Lord Cathcart, an annual pension of £200 Sterling and the right to reside in the castle, and £150 Sterling was provided by the Treasury for the King’s Master of Works, Sir Archibald Murray of Blackbarony, 3rd Bt., to undertake “absolutely necessary” repairs. It isn’t clear if Lord Cathcart, who died in 1709, took up residence in the castle however.

In December 1706 Daniel Defoe reported that an anti-Union mob had taken possession of the castle, and in 1715 the Great Tower was used to house 300 Jacobite prisoners. The Crown had leased the revenues of the archbishopric to the University of Glasgow from 1697 in return for an annual fee however this didn’t include the castle and it seems that this may have contributed to its downfall. Without a local Crown official overseeing the property of the archbishopric the castle began to be used as a source of materials for local building work.

In 1715 Robert Thomson, postmaster of Glasgow, approached Mungo Graham of Gorthie, factor to James Graham, 1st Duke of Montrose, with a proposal regarding the castle. The Duke had in 1704 acquired the Scottish estates of Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Richmond and 1st Duke of Lennox (second creation), and in 1714 had been appointed bailie of the barony and regality which had belonged to the archbishopric. Thomson proposed that the Duke should obtain a grant of the castle from the Crown and then rent the “house and ground right” to him for 1000 merks.

The Duke doesn’t seem to have pursued the opportunity however he did have some interest in the castle as his factor held some of the keys for it. It may be that some ownership or right had passed to the Duke with the properties of the Duke of Lennox.

In 1726 Thomson petitioned the Court of Exchequer in Edinburgh regarding the theft of materials from the castle. A survey was carried out by William Adam and the following year Thomson was appointed responsible for the castle and granted the rents from the garden to the north of the castle for the upkeep of the buildings. During 1727 he seems to have embarked on something of a wild goose chase in search of the keys to the various parts of the castle.

He went to Buchanan Castle in an attempt to retrieve keys from Graham of Gorthie, to Cardonald, Ross Hall and Edinburgh in search of keys supposedly held by Lady Blantyre, and asked John Graham of Dougalston, a commissioner for the Duke of Montrose, who held the key of a high room in one of the towers,

Two years later he requested permission to sell some stones and materials but evidently the response was either not to his liking or too slow for in 1730 he was accused in an anonymous letter of removing ironwork, stone and timber from the site for sale.

Despite this Thomson seems to have remained in his role for several more years until he was replaced with Robert Molleson, an excise officer in Ayr. In 1735 Andrew Ramsay, Lord Provost of Glasgow, reported that the castle consisted of nothing “but a ruinous heap of stones and a great part of rubbish”. Molleson seems to have encountered some resistance to his efforts to preserve the castle and it continued to be used a source for materials.

In 1736 a stonemason and his two accomplices were caught in the act of destroying demolishing the staircase to the chapel. Later that year a large part of the Great Tower fell and another part was described as “a frightfull wall which hangs over the main street”.

It seems that the castle was deemed beyond saving by this time and in 1741 John Cochrane of Waterside, grandson of William Cochrane, 1st Earl of Dundonald, was granted a lease of four terms of 19 years at a cost of £3 10s a year with plans to build a linen manufactory within the castle’s boundary approved. He later admitted that he had obtained the lease on behalf of his cousin, Major Thomas Cochrane, later 8th Earl of Dundonald, and the linen manufactory was never built.

In 1744 Cochrane notified the Town Council of a proposal to return the site to the Crown to allow a barracks to be built within the castle, although nothing seems to have come of this. In the same year there was said to be “nothing standing but a few old walls” however a drawing from 1748 shows substantial ruins with both Cameron’s and Beaton’s towers standing almost to their full height.

R Williams, 1812image courtesy of Glasgow Museums

OG.1951.409.wb

Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Edinburgh, 1890

In 1755 permission was granted to Robert Tennent for some stone to be taken from old buildings in the area for use in the construction of the Saracen’s Head Inn on Gallowgate. Some sources state that the stone in question came from the Gallowgate Port or East Port however Tennent was said to have removed the arms of Bishop Dunbar and James Houston from the gatehouse around 1760 and built them into the back of a tenement he was building at 22 High Street. This would suggest that Tennent used stone from Bishop Dunbar’s gatehouse. By 1758 Major Cochrane was said to have “pulled the building to pieces in order to sell the stone”.

Thomas Girtin, c.1797image courtesy of Tate

© Tate

CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)

In 1778 part of the ruins were removed in order to widen Castle Street and by 1780 the gatehouse roof had fallen in, the upper floor of its north tower collapsed and the south tower had been reduced to ground floor level. At this time the south-east wall of the castle was intact apart from a breach to the south of the gatehouse, and Beaton’s tower at the south-west corner of the castle still stood to its full height complete with its roof and caphouse.

In 1784 a committee was appointed to investigate the possibility of obtaining the lease from the Cochranes and for the city to take ownership of the castle. The site was chosen in 1788 as the ideal location for a new infirmary and a committee was set up to negotiate with Archibald Cochrane, 9th Earl of Dundonald. An application was made to the Treasury and Court of Exchequer for permission which was granted in 1791.

Work commenced on removing the remaining ruins and by 1791 the Great Tower was a shell, the basement vault having collapsed and the tower’s west wall having fallen, while the gatehouse had been reduced to a pile of rubble. The Royal Infirmary was built from 1792 and opened in December 1794.

Some parts of the castle still survived into the 19th century however. In 1853 the old castle’s mound in front of the new Infirmary was flattened and its silted-up ditch was noted. The remains of a drawbridge were uncovered during the process, constructed from twelve beams of pegged oak. Part of the round tower at the north-west of the courtyard wall still stood until that year (at approximately NS 6011 6558), with ten steps leading down into a basement chamber. The remains of a tower at the head of Kirk Street, an old street which connected the High Street to Castle Street just north of the junction with Cathedral Square (around NS 6011 6551), required dynamite to remove such was their strength.

In 1880 a heraldic stone and a carved wooden panel, variously described as oak or walnut, from the castle were in the possession of the Glasgow Archaeological Society, while the arms of Bishop Dunbar and James Houston were saved by Bailie Millar, the owner of the tenement in the High Street when it was demolished, and given to Sir William Dunbar who took them to Mochrum. A 21m long section of the castle’s north wall was said to still exist under the Chronic Surgical House of the the Royal Infirmary in 1886.

By 1888 a stone carved with the arms of Archbishop Beaton was to be found in the porch of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church on North Woodside Road. This had been built into the front wall of an old house on the same road which was demolished in 1869.

In 1971 excavations revealed fragments of walling from the castle and associated late medieval pottery. The ditch observed in 1853 was found and it was speculated that it might date to the 13th or possibly even 12th century.

Archaeological excavations were carried out from late 1986 to early 1987 ahead of the construction of the St Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art. The remains of part of Archbishop Beaton’s courtyard wall were uncovered, along with part of his Bishop’s Palace at the south-west corner of the castle. The remains of the tower survived to a height of four courses with a mix of well-dressed ashlar and roughly-shaped stone and a rubble infill. On one of the stones a mason’s mark in the shape of a stylised fish was found. The tower and wall were deemed to be contemporary, and 13th and 14th century green glazed earthenware and post-medieval pottery was also discovered.

To the north of St Mungo’s Museum the site of Bishop Cameron’s Great Tower is now marked by a granite pillar, erected in 1913 and constructed of stone taken from the castle. On the north side of the pillar were two bronze panels, now removed, the upper of which was inscribed with an image of the castle and the lower of which carried the following legend:

PRESENTED TO THE

CORPORATION OF GLASGOW

BY FRANCIS HENDERSON ESQ

LORD DEAN OF GUILD OF THE CITY

IN THE YEARS 1910-12

TO MARK THE SITE OF THE BISHOP’S PALACE

WHICH WAS BUILT IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY

AND WAS FINALLY REMOVED IN 1792

A second panel to the south is fixed within a circular arrangement of cobbles next to St Mungo’s Museum and marks the site of the castle’s 16th century well.

The arms of Bishop Dunbar and James Houston are now housed in the crypt of the Cathedral.

Alternative names for Glasgow Castle

Archbishop's Palace; Archepiscopal Palace; Bishop's Castle; Bishop's Palace; Castell of Glasgow; Castill of Glasgow; Castle of Glasgow; Episcopal Palace