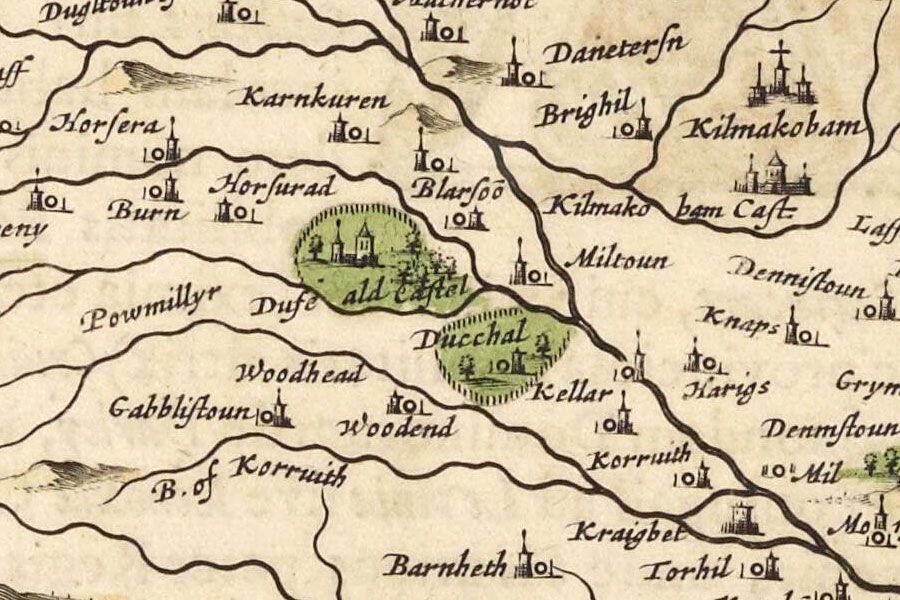

Joan Blaeu, 1654map image courtesy of NLS

Duchal Castle, of which only a few fragments remain, stands on a rocky outcrop between the Green Water and the Blacketty Water.

The lands of Duchal were owned by the Lyle family from at least the 12th century, with a Radulphus or Radulfus de Insula, progenitor of the Lyle name, described as “dominus de Duchal” in 1170. The Lyle surname is said to derive from “de Insula” being translated into French as “de L’Isle”. Radulphus, anglicised as Ralph, may have travelled to Scotland with Walter fitz Allan and is said to have built the first castle at Duchal around 1164.

While it’s possible that a castle was built here in the 12th century it may be that the first Lyle castle was Duchal motte. The earliest remaining parts of Duchal Castle have been ascribed to the 13th century, although they may have replaced an earlier structure.

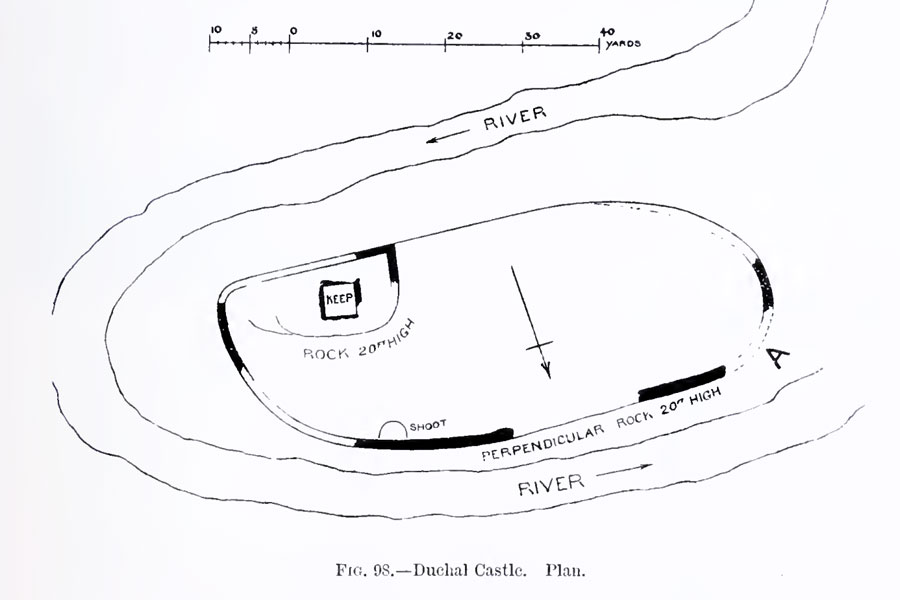

Although the castle occupies a low-lying position it was defensively very strong at the time of its construction, before the advent of artillery. Standing on a narrow peninsula of land bounded to the north by the Green Water and to the south by the Blacketty Water, it is protected by 8 metre deep ravines through which the rivers flow.

David MacGibbon & Thomas Ross, Edinburgh, 1889

On the west side, the entrance to the promontory, a deep ditch was cut across the peninsula isolating the castle entirely from the surrounding land. It has been suggested that this ditch may have connected the two rivers forming a moat around the castle. It’s original dimensions are unknown as it has been partially filled in, at the south end in particular. However a section around 15m long still survives at the north which is between 4 and 6 metres wide and varies from 0.5m to 1.5m in depth.

The castle is aligned approximately east to west and covers most of the surface of the promontory, which measures around 64 metres east to west by around 25 metres north to south. The majority of the site was flat and enclosed by a thick enceinte wall, thought to date to the 13th century.

The entrance was probably through a gatehouse at the north-west corner of the site. Foundations suggest that this building measured around 6m by 6m, and a small section of the north wall of the it can still be seen standing to a height of around 1 metre. It was defended by gunloops on the north side which were probably added early in the 16th century.

One of these points north while the other is smaller in size points west along the wall face. It has been suggested that the latter may be some kind of drainage channel, although it’s position does suggest it being a defensive feature.

The internal face of a section of the west wall, part of the curtain wall, can also be seen although the exterior face is is obscured by earth and undergrowth. It measures around 14 metres long, forming the north end of the west wall, around 1.5 metres thick and varies in height between 1 and 1.5 metres.

Not much of the north section of the curtain wall remains beyond that forming the north wall of the gatehouse. A small section of the curtain wall stands at the north-eastern corner of the site next to a deep, steep-sided hole which has been interpreted as a draw-well.

Only a small section of the east wall survives, containing the upper lintel and sides of another wide-mouthed gunloop and a piece of worked stone which may represent part of a garderobe chute.

At the south-east corner of the site is a rocky outcrop upon which a tower was built, surrounded by a wall. The rock is steep sided and rises at least 2 metres above the inner bailey to the north and around 4 metres above the outer bailey to the west. The outcrop is less precipitous on the south-east side which is likely where the tower was accessed from.

The footings of the tower show that it was aligned approximately north-west to south-east, rectangular in plan, and measured around 11.5 metres in length by around 9 metres wide north-east to south-west. The majority of the north-east side of the tower has gone however substantial sections of the south wall still stand to a height of around 2 metres. There may have been a tower on this rock contemporary with the curtain wall, however the remains are thought to be of a 15th century tower.

The Lyles were a notable family, and in 1445 Robert Lyle was created Lord Lyle by James II. His son, also Robert Lyle, 2nd Lord Lyle, was a trusted associate of James III and a lord of the privy council. Following the death of the King in 1488 Lyle was named one of the lords of the privy council to the infant James IV and was appointed Lord High Justiciar of Scotland.

However he later joined the rising against the young King led by the Earl of Lennox, and held Dumbarton Castle for the rebels. James IV marched his soldiers to Lennox’s Crookston Castle and besieged and took it. They then laid siege to Duchal Castle, bringing two huge cannons with them. One was the celebrated Mons Meg, which now stands on the battlements of Edinburgh Castle, while the other, since lost, was later named Duchal.

Whether or not the cannons were fired at Duchal is unknown, however the castle surrendered and the Lyles briefly forfeited their estates. Duchal Castle was put in the care of Robert Cunningham, 2nd Lord Kilmaurs and later 2nd Earl of Glencairn. However James the punishment was a relatively short one and Duchal was restored to Lord Lyle in 1491.

Subsequently James IV often stayed at Duchal Castle when visiting Renfrewshire, and one of his mistresses, Marion Boyd of Bonshaw, gave birth to their son at Duchal Castle in 1497. The King celebrated his twenty-fifth birthday at Duchal on the 17th of March 1498.

Robert Lyle’s grandson, John, 3rd Lord Lyle, sold Duchal to John Porterfield of Porterfield in 1544. Following the death of John Porterfield in 1575 his second wife, Jean Knox of Ranfurly, retired to their old seat of Porterfield which the family now used as a dower house.

In 1578 James Cunningham, Master of Glencairn (later the 7th Earl of Glencairn), attacked and burnt down Duchal Castle as part of a feud between the Cunningham and Porterfield clans which went on for a couple of years. It was presumably rebuilt as it is marked on Timothy Pont’s map of Renfrewshire, published some time between 1583 and 1596.

In 1701 Duchal Castle was described as being partly ruinous, and by 1710 the Porterfields had moved into Duchal House, or “New Duchal”, around 2 kilometres to the east-south-east of Duchal Castle. Alexander Porterfield is said to have built Duchal House in 1710 as his wife Lady Catherine Boyd, daughter of the Earl of Kilmarnock, found the old castle to be damp and unsuitable for modern living.

However, as well as the reference to the castle being ruinous in 1701, in Blaeu’s Atlas, published in 1654, “Ducchal” appears along with “ald Castel” (Old Castle) presumably representing the new house and Duchal Castle respectively. Both are surrounded by palisades and coloured green denoting important buildings. This suggests that Duchal House is older than generally thought.

At the same time as the construction of the new house a summerhouse was built on the River Gryfe using stones from the old castle. As the castle was being dismantled human bones were discovered in an upper chamber.

The castle was considered notable enough to be included on Herman Moll’s map of The Shire of Renfrew in 1745, but by 1782 the castle had been reduced to substantial ruins although the old drawbridge and well still existed at that time. The castle is also marked on John Ainslie’s Map of the County of Renfrew, published in 1800, and in John Thomson’s Atlas in Scotland, published in 1832.

Following the death without an heir of James Corbett Porterfield in 1855 the estate passed to Sir Michael Shaw-Stewart, 7th Baronet of Ardgowan, whose mother was Margaret Porterfield.

The Shaw-Stewarts used Duchal House as a shooting lodge. They sold Duchal in 1910 to a George Wallace who in 1913 or 1915 sold it Joseph Paton Maclay, 1st Baron Maclay, whose descendants still own the property.

Alternative names for Duchal Castle

Dowchill; Douchale; Dowchale; Dowchall; Dowquhale; Ducchal; Ducchall; Duchal Old Place; Duchale; Duchall; Duchell; Duchyl; Old Place of Duchall